The problem of economics in developing nations has always been a very complex equation that no theorist has been able to solve. However disparities between agrarian and industrialized economies and how they can relate and balance each other has its roots in the theories of economist William Arthur Lewis.

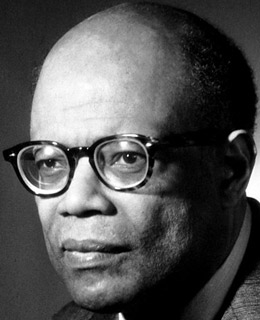

Born in 1915 in St. Lucia, Lewis saw firsthand the economic imbalances shouldered by the poor in developing nations. Although a British colony, his country was stricken by abject poverty. An excellent student, he attended the London School of Economics and quickly became professor at the University of Manchester.

At Manchester, the influx of Asian and African students spawned a deeper interest in learning about the economies of their nations. While traveling through Bangkok in 1952, Lewis realized that for the most part wages in poor nations stayed constant while profits soared, which went against the assumption that an investment increase should raise wages and stabilize the capital return rate.

Both problems had the same answer: demographics. It turns out that developing nations were divided into two parts: a traditional agricultural sector that had an abundance of labor but low wages and productivity; and a modern industrial sector which carried higher wages and higher productivity but more demand for labor. Profits continue in the latter as long as investment continues. If labor transfers from the traditional to the modern sector, eventually both production and wages will equalize.

This meant that the fixed labor supply was not really relevant to poor nations with lots of underemployed workers. But if there were dual sectors, it would help the economies of poor countries in the long term because manufacturing, which had a labor shortage, could pull from agricultural, which had an overabundance.

This concept was termed the "Dual Sector Model" and was catalogued in Lewis' signature work Theory of Economic Growth in 1955. Although controversy and debate dogged him throughout his career, these and other theories are now seen as the beginnings of international development economics. Lewis continued on the path of advocating development in poor nations. He was named principal of the University of the West Indies and later became an economic adviser to the fledgling nation of Ghana. He was knighted in 1963.

In 1970, Lewis helped form the Caribbean Development Bank, based in Barbados, which lent money to borrowing member nations to improve their economies based largely on the Dual Sector Model. In 1979, while teaching at Princeton University, he won the Nobel Prize for economics for his pioneering research on developing nations, the first black person to win a Nobel aside from the peace prize. In 1983, he retired and became president of the American Economics Association, where he remained until his death in 1991.